Orphaned Peace in a Warming Land

Ramadhan and the Bangsamoro Struggle for Self-Determination

Ramadhan Kareem to our Muslim brothers and sisters.

Ramadhan is observed through fasting from dawn to sunset — a discipline meant to cultivate restraint, moral clarity, and solidarity with those who hunger. But fasting is not only about abstaining from food and drink. It is about examining power, responsibility, and justice in both personal and public life. The Qur’an reminds believers to “stand firmly for justice, even against yourselves” (4:135), a principle that extends beyond private faith into public accountability.

In Bangsamoro, where communities continue to experience displacement, insecurity, and unresolved injustices, Ramadhan sharpens an urgent question: are the commitments made in the name of peace being honored in practice?

The Bangsamoro peace process is not collapsing in spectacle. It is thinning quietly — through delay, reinterpretation, and uneven implementation. Quiet deterioration is easier to normalize — until it becomes irreversible.

That makes it more dangerous.

Marawi: Where Peace Is Measured

Before dawn in a transitory shelter in Marawi, a mother wakes her children for suhoor. The structure was meant to be temporary.

It has now stood for eight years.

The 2017 siege displaced more than 350,000 people and destroyed roughly 95 percent of the city’s core. According to reporting and official monitoring cited by Rappler and local recovery agencies, around 70,000 people remain displaced. Of roughly 14,000 compensation claims filed with the Marawi Compensation Board, only about 1,100 had been approved for payment as of late 2025.

Roads have been rebuilt. Government buildings stand. A lakeside promenade gleams.

Yet many families still cannot return. Compensation remains pending. Land tenure disputes persist. Physical reconstruction has advanced faster than restitution.

Marawi is not simply a rehabilitation site. It is the clearest test of whether the 2014 Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) will translate into lived justice.

Peace agreements are measured not only by infrastructure completed, but by rights restored.

When restitution lags behind reconstruction, trust erodes quietly.

What the Moro Struggle Was Always About

The Bangsamoro peace process did not begin in 2014.

It is rooted in centuries of resistance — from Spanish colonial campaigns in Mindanao, to American pacification policies, to post-independence land settlement programs that transferred vast tracts of ancestral territory to settlers, corporations, and political elites. In the 20th century, organized Moro movements emerged in response to land dispossession, militarization, and political marginalization — dynamics documented extensively in Moro historiography and human rights reporting.

At its core, the Moro political struggle has consistently centered on self-determination: the right to govern ancestral territories, protect land from dispossession, and seek justice for historical and continuing abuses.

From the Jabidah massacre of 1968 — which catalyzed modern Moro resistance — to the militarization of Mindanao under martial law, from repeated waves of mass displacement to structural poverty in resource-rich provinces, the demand was not merely for inclusion within centralized governance. It was for meaningful autonomy anchored in land, dignity, and political authority.

The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) was meant to respond to that historical arc — not simply to silence guns, but to address the structural roots of conflict.

For many Bangsamoro communities, autonomy was intended as correction: of land injustice, of centralized political control, and of the long denial of collective self-governance.

The Integrity of the Transition

The Bangsamoro Organic Law envisioned a transition led by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), reflecting the negotiated understanding that those who laid down arms would guide the region toward democratic governance.

In March 2025, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. replaced MILF Chairman Al Haj Murad Ebrahim as Interim Chief Minister of the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA). MILF leaders have publicly expressed concern that the decision did not reflect endorsement from the MILF Central Committee. MILF-BIAF Chief Abdulrauf “Sammy Gambar” Macacua was subsequently appointed, alongside adjustments in parliamentary composition.

Under the transition framework, the President retains appointment authority.

Politically, however, such decisions are interpreted through history.

In a region where leadership fragmentation has historically intersected with counter-insurgency strategies, developments that alter negotiated political balance inevitably raise questions among some sectors about whether the integrity of the transition remains intact.

The issue is not about personalities.

It is whether the architecture of negotiated self-determination remains faithful to the spirit in which it was agreed.

Peace agreements endure not only because they are lawful, but because they are perceived as reciprocal.

Militarization and Normalization

The peace process included not only decommissioning of MILF combatants, but normalization — a recalibration of security posture and governance structures to reflect transition from armed struggle to civilian authority.

MILF statements in mid-2025 indicated the suspension of decommissioning of roughly 14,000 remaining combatants and 2,450 weapons, citing concerns about balance in implementation. Monitoring mechanisms have previously confirmed that more than 24,000 combatants had already completed decommissioning. Around 26,000 former combatants continue to await full delivery of socio-economic packages.

At the same time, communities and local monitors continue to report military operations in parts of the Bangsamoro, including areas historically associated with former MILF strongholds. The government maintains that operations target criminal or extremist groups. Yet the persistence of militarized activity in a region transitioning toward autonomous governance complicates perceptions of normalization.

Normalization is not a one-sided obligation.

It requires transformation of both non-state and state security frameworks.

A Region Under Reassessment

In recent weeks, the MILF has convened assemblies across the Bangsamoro region — in Basilan, Lanao del Norte, Maguindanao del Norte, Cotabato, the Special Geographic Area, and in Darapanan. These gatherings have brought together political officers, base commanders, members of the armed component, and ordinary members.

These are not ceremonial meetings.

They are moments of reassessment within a fragile transition.

Legal avenues are being explored. Debates continue inside the Bangsamoro Parliament. Organizational consultations are unfolding within the movement.

Bangsamoro society is not monolithic. Views differ across sectors. Some interpret recent developments as political recalibration. Others view them through long memory of central interference. Many are focused less on leadership disputes and more on elections, livelihoods, floods, and compensation delays.

What unites these perspectives is sensitivity to whether the promise of genuine self-determination is being deepened or diluted.

In fragile transitions, perception carries political weight.

Climate Fragility and Layered Displacement

All of this unfolds in one of the most climate-vulnerable regions in the country.

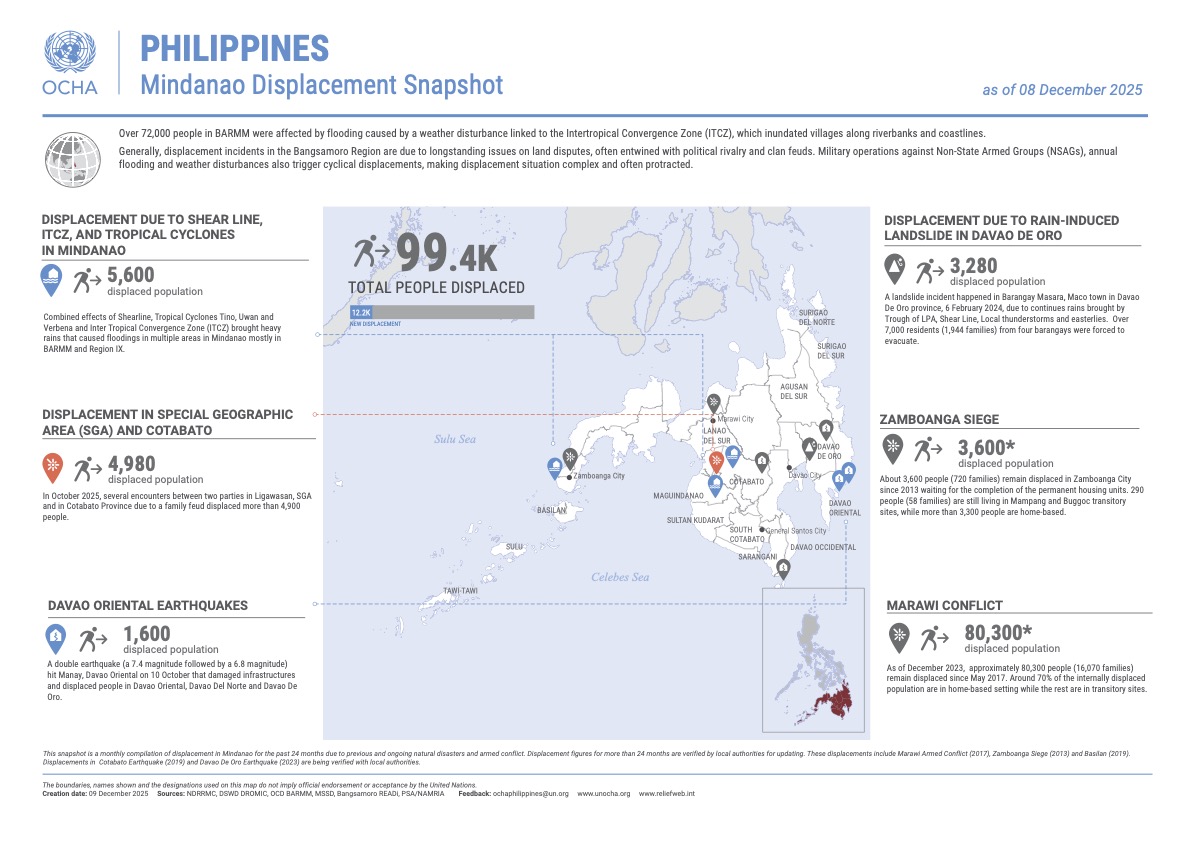

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Mindanao Displacement Snapshot (December 2025), nearly 100,000 people remain displaced across Mindanao, including tens of thousands in BARMM affected by seasonal flooding, clan conflict, and protracted displacement from Marawi.

Conflict displacement and climate displacement overlap geographically.

Communities displaced by war often resettle in flood-prone areas and degraded watersheds. In Lanao del Sur, deforestation and illegal mining have worsened flood risks. In Tawi-Tawi, saltwater intrusion threatens fisheries. In Basilan, agricultural losses strain already fragile livelihoods.

Climate and energy policy scholar Dr. Laurence Delina has identified BARMM as among the most climate-and-conflict susceptible regions in the Philippines, warning that climate shocks act as threat multipliers in politically fragile settings.

Peace scholar Prof. Rufa Cagoco-Guiam has long argued that environmental destruction in Mindanao is never socially neutral — its burdens fall first and hardest on the poor.

This vulnerability is further compounded by land conversion, plantation expansion, and extractive projects that degrade watersheds while concentrating benefits.

Peace without climate justice is unstable.

Climate resilience without political justice is unsustainable.

Indigenous Peoples in the Bangsamoro: Land, Law, and Layered Self-Determination

The question of self-determination in BARMM does not concern Moro communities alone.

The region is also home to Teduray, Lambangian, Dulangan Manobo, Erumanen ne Menuvu, and other Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples (NMIPs), whose ancestral domain struggles long predate the current political transition — and even the contemporary Bangsamoro framework. Some Teduray identify as Muslim, others as Christian, and others maintain Indigenous spiritual traditions — a reminder that identity in Mindanao resists simple binaries.

For many Teduray families, ancestral land claims are not abstract legal petitions but daily questions of security and survival.

At the Mindanao Climate Justice and Solidarity Conference, Allan T. Olubalang — Timuay “Titay” Bleyen of Timuay Justice and Governance — described the Timuay system as a collective Indigenous governance tradition rooted in justice, participation, and deep ecological stewardship. In this worldview, land and rivers are entrusted responsibilities. “We are stewards, not owners.”

Yet ancestral domain recognition within BARMM remains uneven. According to data compiled by Climate Conflict Action and reported by MindaNews, at least 102 non-Moro Indigenous individuals were killed in the Bangsamoro region between 2019 and 2025 in incidents arising from a mix of land disputes, rido, armed violence, and localized conflict dynamics. In 2024, regional media reported the killing of Teduray elder Ramon Lupos in Maguindanao del Sur, a case widely reported and condemned by officials who pledged investigation.

These incidents underscore the continued vulnerability of some NMIP communities even within an autonomous framework that formally recognizes their rights.

The Bangsamoro Indigenous Peoples Act (BIPA) marked an important institutional milestone in recognizing IP rights within the region. However, Indigenous advocates have pointed to implementation gaps, overlapping land classifications, delays in formal ancestral domain recognition, and persistent insecurity as ongoing challenges. BARMM officials, for their part, have cited institutional and jurisdictional complexities during the transition period.

In response to extractive pressures and environmental degradation, initiatives such as FUSAKA INGED Task Force Bantay Kalikasan have mobilized communities under a clear message: “Do not mine our future.”

These struggles are not external to the Bangsamoro project. They are internal tests of it.

If autonomy was meant to correct historical injustices, it must also ensure that Indigenous Peoples within BARMM experience meaningful protection, participation, and recognition of ancestral governance systems such as the Timuay.

Autonomy must not reproduce internal inequities.

Layered self-determination — Moro and Non-Moro alike — strengthens the legitimacy of the Bangsamoro experiment.

The Youngest Region in the Country

BARMM has the youngest population in the Philippines. A significant share of its residents are under 25 — a generation that grew up amid conflict, witnessed the promise of the 2014 Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro, and participated in the plebiscite that ratified autonomy in 2019.

For many young voters, autonomy was not symbolic. It carried the expectation that governance would change in substance, not merely in name.

Yet postponed parliamentary elections, stalled normalization processes, and persistent insecurity shape how that generation now understands democracy. When transitional arrangements extend indefinitely, participation begins to feel suspended. When promised socioeconomic support is delayed, trust erodes quietly.

In a region where climate shocks repeatedly disrupt schooling, livelihoods, and community stability, young people experience fragility not as theory but as lived reality. Displacement interrupts education. Flooding reshapes opportunity. Political uncertainty compounds vulnerability.

For Bangsamoro youth, self-determination cannot remain permanently transitional.

Legitimacy cannot be prolonged through appointment alone.

It must be renewed through participation, delivery, and a clear, credible electoral timetable that affirms the right of the Bangsamoro people to choose their representatives.

The durability of peace depends not only on agreements signed, but on whether the next generation believes those agreements still matter.

Duyog Ramadhan: Accompaniment Across Faiths and Flooded Communities

In Mindanao, Duyog Ramadhan — literally “accompanying Ramadhan” — refers to a longstanding tradition of solidarity during the holy month. More than a shared meal, Duyog centers on accompaniment: Muslims and Christians gathering at sundown for iftar, standing together in mutual respect and shared struggle.

The practice emerged in the late 1970s in Muslim-Christian communities amid political tension and armed conflict between the Philippine state and Moro movements. At a time when mistrust and violence shaped daily life, Christian churches sponsored community iftar meals in solidarity with Muslims observing the fast. By 1984, Duyog Ramadhan explicitly called attention to the shared struggles of Muslims and Christians for dignity, peace, and self-determination in Mindanao. It was not charity. It was a declaration that justice was a collective responsibility.

This tradition continues.

On the first day of Ramadhan, February 18, 2026, Kinaiyahan Mindanao, Mindanao Climate Justice (MCJ), the Panaad Network – Pilgrims for the Earth and People, the Anavah Committee, and the MSU Communication and Media Studies Department, conducted Duyog Ramadhan in solidarity with families affected by Typhoon Basyang in Iligan City.

Assistance was delivered to Muslim communities in Barangay Tipanoy and Barangay Puga-an — areas that have repeatedly endured flooding and displacement, recalling earlier disasters such as Sendong and now Basyang. For many residents, Ramadhan unfolded not in restored homes but in fragile conditions shaped by both climate vulnerability and structural inequality.

The initiative combined material support with presence. Youth volunteers, faith leaders, and community members gathered with affected families before iftar, shared meals, and listened to stories of loss and resilience. In doing so, they carried forward a tradition where faith practice is inseparable from social responsibility.

Yet Duyog Ramadhan does not replace state obligation. It reflects the conviction that solidarity must accompany justice — and that community care must move alongside institutional accountability.

In a region where climate disasters intersect with unresolved political transitions, accompaniment becomes both spiritual discipline and civic commitment.

A National Test

Bangsamoro is not a peripheral concern in a country already strained by climate disasters, political uncertainty, and uneven development.

If the integrity of the peace agreement weakens — with normalization stalled, thousands of former combatants still awaiting promised socioeconomic support, and political trust eroding — while climate shocks intensify in one of the nation’s most vulnerable regions, the consequences will not remain local. They will surface in renewed displacement, mounting security pressures, and growing doubts about the Philippine state’s reliability in honoring negotiated settlements.

What happens in Bangsamoro does not stay in Bangsamoro.

In a climate-changed nation, weakened peace compounds vulnerability. Displacement becomes cyclical. Fragility becomes structural.

The space for corrective action still exists.

But it narrows when political attention turns elsewhere and commitments are treated as optional.

Ramadhan and Responsibility

Ramadhan teaches restraint — and reminds those entrusted with power that responsibility cannot be deferred.

Families in Marawi breaking their fast in temporary shelters eight years after the siege are not asking for charity. They are asking that promises already made be kept.

Justice delayed in Bangsamoro does not remain regional. It reshapes the nation.

In a warming land, peace will endure only where justice is practiced — not postponed.

Ramadhan Kareem.