Part 1: Grounding in Faith, Struggle, and Frontline Realities

November 27, 2025 · Diocesan Pastoral Center, Impalambong, Malaybalay, Bukidnon, Mindanao, Philippines.

Day 1: Context, Testimonies, and Collective Resolve

Lumad and Moro leaders, Indigenous and peasant communities, youth organizers, parish workers, clergy, women human rights defenders, and civil society groups from across Mindanao gathered in Malaybalay for the Mindanao Climate Justice & Solidarity Conference 2025.

Convened by the Diocese of Malaybalay, Mindanao Climate Justice (MCJ), PANAAD Network of Care, and Kinaiyahan Youth, the three-day assembly deepened shared analysis of Mindanao’s crises and strengthened collective commitment to defend land, life, and self-determination.

From the outset, the conference made clear: communities are not just victims of crisis—they are protagonists of resistance and renewal.

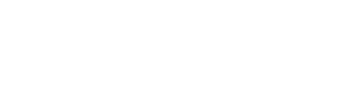

Religious sisters from various congregations share a moment with Bishop Jose Manguiran before the program begins—signaling the strong faith-based solidarity that continues to accompany Lumad, Moro, and rural communities in their struggles for land and life.

Religious sisters from various congregations share a moment with Bishop Jose Manguiran before the program begins—signaling the strong faith-based solidarity that continues to accompany Lumad, Moro, and rural communities in their struggles for land and life.

Opening: Rooted in Prayer, Memory, and Shared Responsibility

The conference opened with an interfaith prayer led by Lumad, Moro, and Christian representatives, grounding the gathering in gratitude to the Creator and remembrance of communities who could not be present—those displaced, threatened, or silenced.

In his welcome, Bishop Noel Pedregosa of the Diocese of Malaybalay stressed that responding to the climate emergency is a shared vocation:

“No single sector can face this crisis alone. We must stand together—Church, communities, and civil society—if we are to protect our common home.”

He affirmed the Church’s responsibility not only to speak about creation, but to stand with communities defending forests, rivers, and ancestral domains in the face of threats.

MCJ Executive Director Ms. Victoria Nolasco, in the conference rationale, located the climate emergency within Mindanao’s long history of dispossession and violence:

“The climate crisis does not arrive in an empty space—it strikes communities already displaced, encroached upon, or militarized. To talk about climate is to talk about land, about Lumad and Moro self-determination, about justice.”

Her message framed the conference as a space for shared analysis, mutual care, and collective planning, not as a project owned by any single institution.

Faith, Ecology, and Frontline Realities

Church Leaders on Pastoral Responsibility and Integral Ecology

In the morning plenary, church leaders from Mindanao reflected on the spiritual and political responsibility of faith communities in the climate emergency.

Bishop Raul Dael of the Diocese of Tandag opened with a stark reminder:

“To protect and care for the environment is not an option; it is an imperative.”

He recalled how Lumad schools had been shut down under suspicion and militarization, and how communities defending forests are often the first to be tagged as “enemies” for standing in the way of mining and other extractive projects. Bishop Dael insisted that:

- It is often Lumad communities—not the state—that are the first, most consistent guardians of forests and rivers.

- Large-scale mining and plantations do not happen without government permission, making state accountability central to any credible climate response.

- True ecological conversion (metanoia) requires a change of mind and heart so that we learn to see creation “as Lumad communities see it”—as kin, not commodity.

He invited the participants to exchange a sign of peace, underscoring that peace with creation and peace with communities are inseparable.

Fr. Reynaldo Raluto, Chair of the Integral Ecology Ministry of the Diocese of Malaybalay, followed with a grounded look at Bukidnon’s forests and watersheds, and the faces of poverty in Mindanao.

He described four interrelated forms of poverty—class, culture, gender, and ecology—and reminded participants that the earth itself has become one of the poorest, battered by extraction and neglect. Drawing from recent data, he noted that:

- Only a fraction of Bukidnon’s uplands remain forested,

- Large agribusiness plantations and monocrop agriculture have driven massive land-use change, and

- The small farmers and Indigenous communities who did not destroy the forests are now the ones most exposed to floods, drought, and hunger.

Fr. Raluto stressed that any ecological ministry that stops at “greening” is incomplete:

“When we destroy the environment, we also destroy the relationships of people. Ecological advocacy must also confront dehumanizing poverty and social injustice.”

He ended with the image of rivers and streams converging:

“If we come together—communities, church, and movements—we can become a mighty river of justice for Mindanao.”

Climate, Conflict, and Feminist Climate Justice

Prof. Rufa Cagoco-Guiam, cultural anthropologist and MCJ Board Member, turned the lens to the Bangsamoro, which she described as enduring two storms at once: decades of violent conflict and accelerating climate change.

She emphasized that:

- There is no such thing as a purely ‘natural’ disaster; disasters become deadly because of inequality, exclusion, and bad governance.

- When typhoons, droughts, or floods hit, those harmed first and worst are Indigenous Peoples, Moro communities, and rural barangays already far from services and political power.

- Climate impacts and conflict interact, deepening food insecurity, intensifying displacement, and straining fragile peace processes.

Prof. Guiam introduced the framework of Feminist Climate Justice, where women, girls, and gender-diverse people can flourish on a healthy and sustainable planet. She highlighted four key commitments:

- Redistribution – of resources, risks, and benefits.

- Recognition – of layered discrimination, including land grabbing in ancestral domains and the marginalization of women, persons with disabilities, and those at the peripheries.

- Representation – ensuring women, IPs, and other marginalized sectors are present and decisive in climate and DRRM decision-making.

- Reparation – moving beyond short-term relief toward restitution, rehabilitation, and guarantees of non-recurrence.

She recalled how an IP community in Maguindanao, heavily hit by a typhoon, received late and inadequate assistance, illustrating how social exclusion shapes who lives, who rebuilds, and who is left behind.

Her recommendations included moving away from toxic monocrop plantations, investing in permaculture and climate-resilient agriculture, strengthening local DRRM systems, and ensuring that climate measures are planned with communities, not for them.

Breaktime Conversations and Community Building

Breaktime became an informal forum of its own, filled with laughter and lively exchanges that deepened relationships across communities and sectors.

Community Testimonies: Shared Stories of Hardship and Resistance

In the afternoon, the conference shifted fully to community voices, centering experiences from ancestral domains, evacuation camps, and conflict-affected barangays.

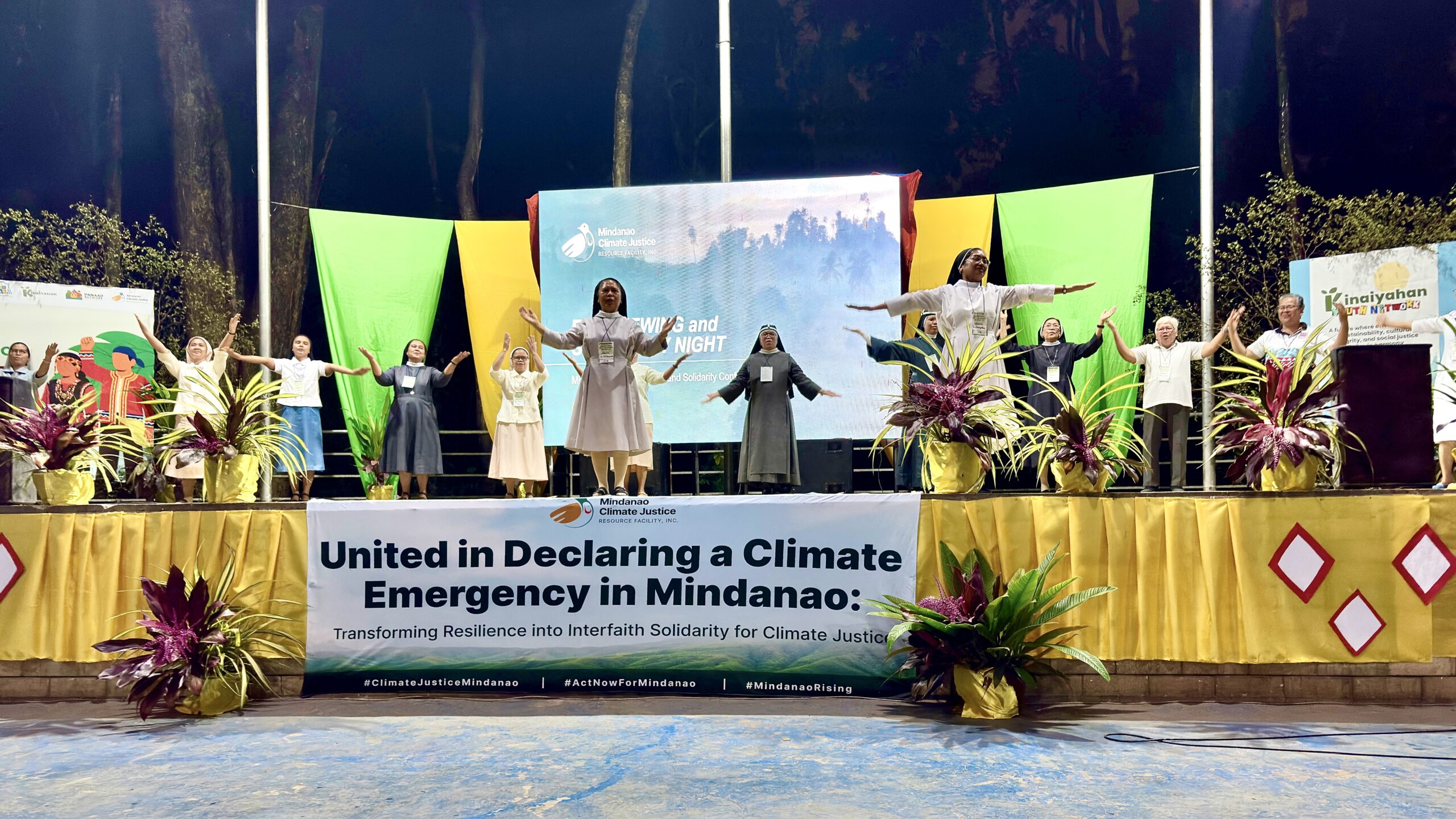

Allan T. Olubalang (Titay Bleyen) of Timuay Justice and Governance shared the long struggle of Teduray-Lambangian and other Non-Moro Indigenous Peoples (NMIP) for their ancestral domain in the Bangsamoro. He described:

- The Timuay system as a collective Indigenous governance tradition rooted in justice, participation, and a deep relationship with nature;

- The understanding that land and rivers are not private property but entrusted responsibilities—“we are stewards, not owners”;

- Ongoing IP killings, displacement, and land grabs, including areas declared for mineral reservation; and

- The creation of FUSAKA INGED Task Force Bantay Kalikasan, which organizes communities to say, “Do not mine our future.”

Despite new policies such as the Bangsamoro Indigenous Peoples Act (BIPA), he stressed that weak implementation and continuing violence keep many Teduray-Lambangian communities at risk. Still, they continue to assert their rights before BARMM institutions and on the ground.

In a recorded message, Prof. Tirmizy Abdullah of MSU Marawi echoed these concerns, reminding participants that displacement is not only physical but also cultural and spiritual. He stressed that development without justice is hollow, and called on churches, communities, and movements to continue standing with Marawi’s displaced families eight years after the siege.

From Marawi, Hanifah Pangcoga of Reclaim Marawi Movement spoke as an internally displaced person:

“Hanggang kailan kami tatawaging IDPs?”

She described families still living far from the city center, paying rent in cramped shelters, struggling with limited water, high transportation costs, and children dropping out of school. For many, “rehabilitation” has meant reconstruction of buildings, not the restoration of people’s lives and dignity.

Through these testimonies—alongside stories from Lumad communities in Bukidnon and other frontline areas—the day traced a common pattern:

- Prolonged displacement and repeated evacuations;

- Land grabbing, “development” projects, and militarized declarations in ancestral domains;

- Collapsing livelihoods, food insecurity, and psychological distress;

- And, at the same time, a stubborn determination to stay rooted in land, memory, and collective struggle.

Synthesis: From Listening to Shared Responsibility

At day’s end, Fr. Arthuro Paraiso, lead convenor of the PANAAD Network of Care, offered a synthesis that echoed the spirit of the testimonies:

“We did not only hear suffering—we heard resistance. Their hardship is not an accident; it is produced by a system that favors a few. Because the forces harming them are systemic, our response must also be organized, united, and rooted in love.”

He emphasized that communities are not seeking saviors. They are asking for katuwang—companions in the struggle, willing to share risk, stand beside them in courts and barricades, and walk with them in the long work of healing, memory, and rebuilding.

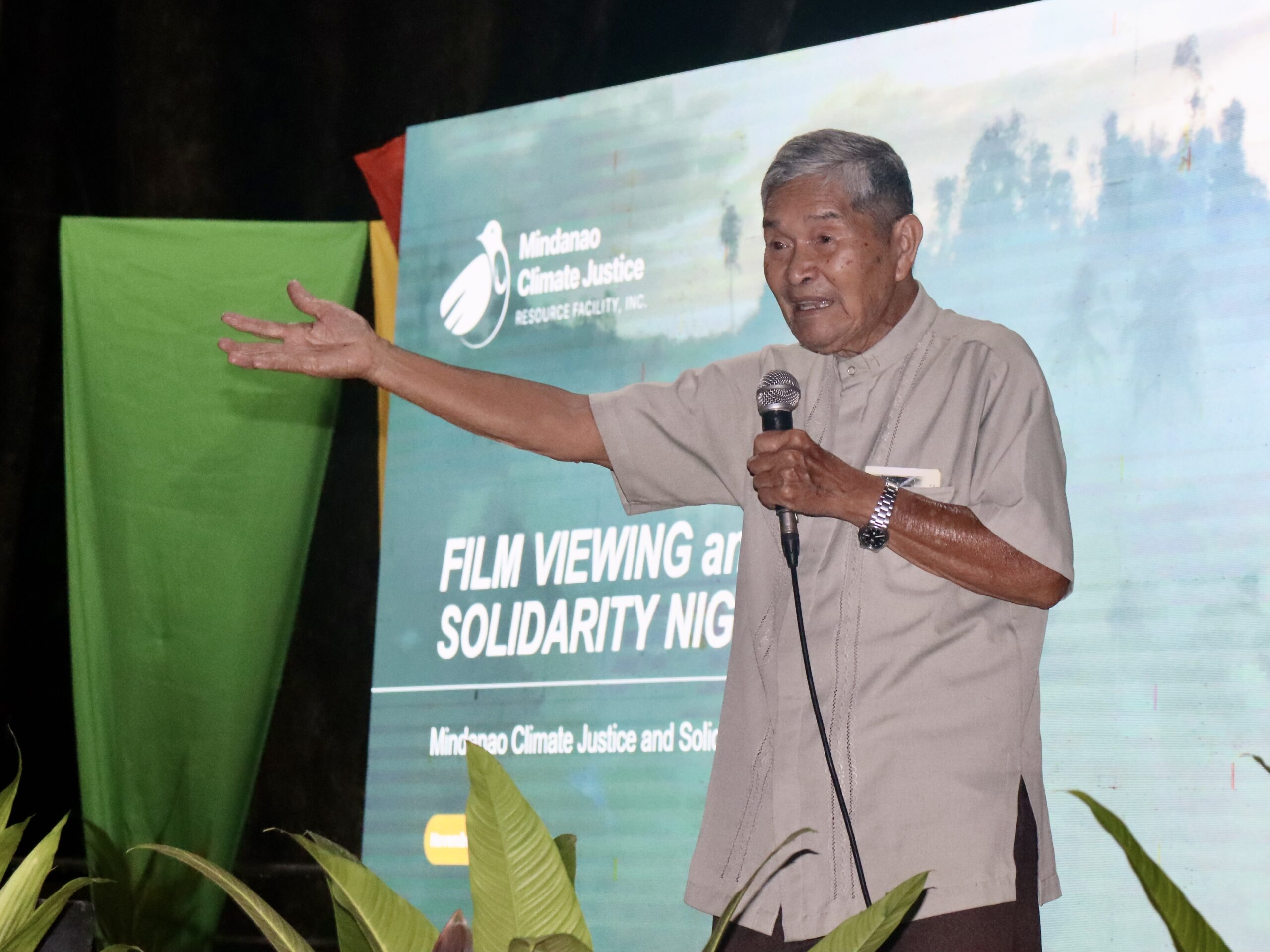

Solidarity Night: Songs of Struggle, Dances of Hope

The first day closed with a Solidarity Night where communities and delegates transformed grief and anger into song, dance, and shared ritual. Lumad and Moro participants offered traditional dances, chants, and stories that carried histories of displacement, survival, and hope. Parish youth and lay workers joined with their own cultural performances, weaving together expressions of faith and struggle.

A highlight of the evening was a special performance by Bayang Barrios, whose songs about land, women, and resistance drew standing ovations. Her voice, rising from and for Mindanao’s communities, reminded everyone that art is not separate from advocacy—it is one of its strongest languages.

As the night ended, participants carried with them not just analysis and data, but the cadence of chants, the rhythm of gongs, and the shared conviction that in Mindanao, climate justice is inseparable from ancestral land, collective memory, and people’s resistance.

Click here to read Part 2: Strengthening Community Capacities and Building a Collective Mandate for 2026