Human Rights Day Forum | December 12

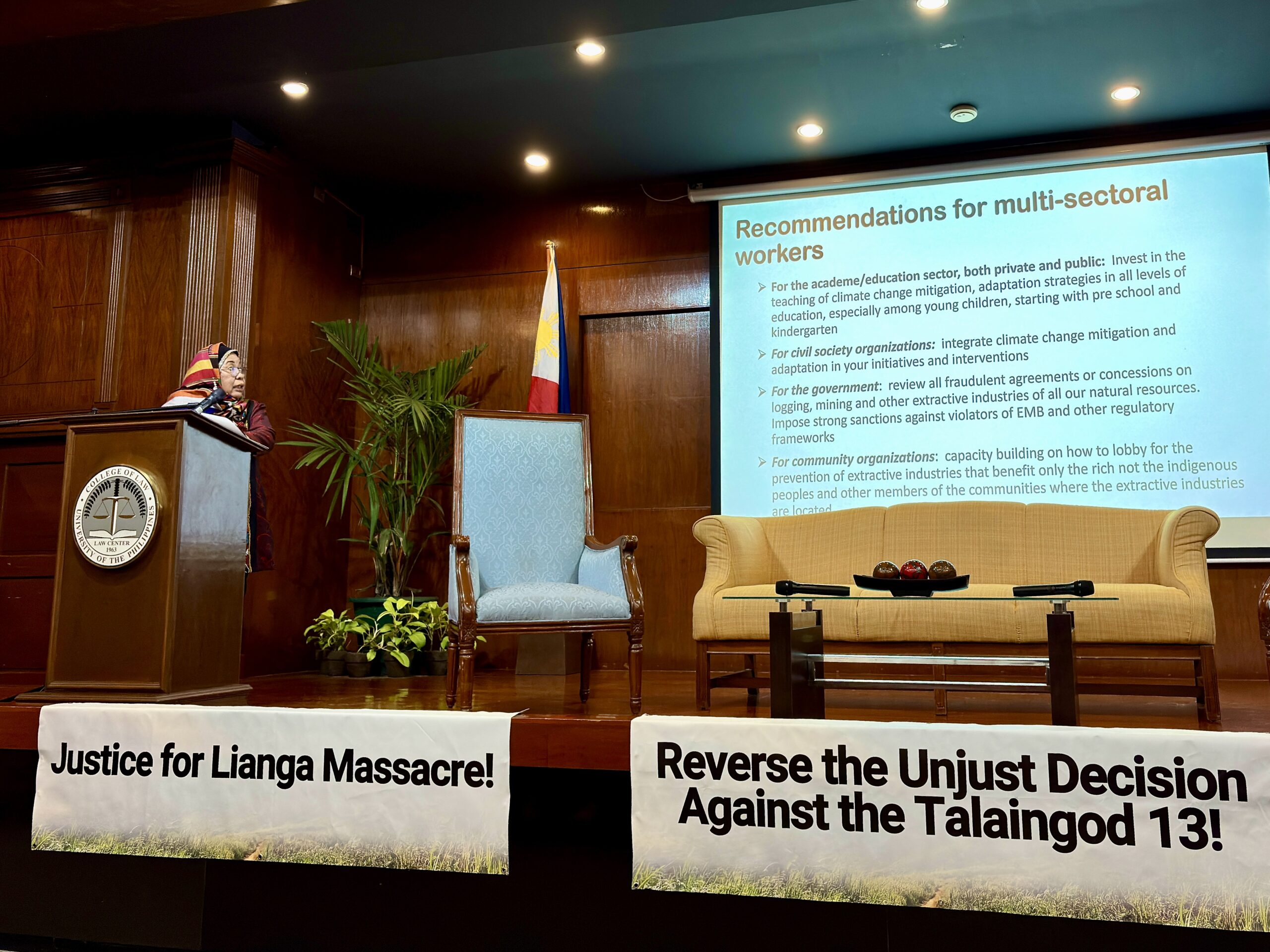

The Human Rights Day Forum Memory, Rights, and Resistance: Stories from Mindanao marked the culmination of a three-day Human Rights Day program that brought Mindanao’s struggles into the heart of the University of the Philippines College of Law. Organized by the UP Law Institute of Human Rights (UP IHR) in partnership with Kinaiyahan – Youth for Climate Justice Movement and Mindanao Climate Justice (MCJ), the program began with a public exhibit and concluded with a forum that insisted on memory not as commemoration, but as resistance.

The exhibit, mounted in the days leading up to the forum, featured photographs, testimonies, and documentation from Marawi, Bukidnon, and Talaingod—places where displacement, land dispossession, militarization, and environmental destruction are not past events but ongoing conditions.

Read about the opening of the Human Rights Day exhibit here.

The forum that followed gave these images and narratives political life: communities spoke for themselves, scholars situated their experiences within broader structures of power, and institutions were challenged to reckon with their responsibilities. Across the day, one message emerged clearly: human rights in Mindanao cannot be reduced to legal language or policy abstractions. They are lived daily—through prolonged displacement, through land rendered inaccessible despite legal recognition, through schools shut down by force, and through ecosystems damaged in the name of security and development.

Human Rights Are Not Abstract

In his welcome remarks, Atty. Paolo Emmanuel S. Tamase, Associate Dean of the UP College of Law, situated the forum within realities that persist long after public and media attention has faded.

“We are gathering not only to celebrate a historic occasion, but to unite communities whose history, struggles, and hopes continue to shape our shared responsibilities.”

He pointed to the unfinished rehabilitation of Marawi more than eight years after the siege, the continuing defense of Indigenous lands in Bukidnon, and the threats and harassment faced by Lumad communities in Talaingod. These, he stressed, demonstrate that human rights violations in Mindanao are not theoretical concerns, but concrete and unresolved injustices.

“The fight for human rights is not abstract. It requires recognition, accountability, and action.”

Following him, Atty. Daniel D. Lising, M.D., LLM, Officer-in-Charge of UP IHR, emphasized that the forum was not merely an academic exercise but part of a longer institutional and community commitment.

“Human rights advocacy is never limited to theoretical thinking. It is alive, protected, and often carried through great sacrifice.”

Situating the forum as the culmination of the three-day program, Lising described remembrance as an act of struggle—one that challenges violence, denial, and erasure. He reaffirmed UP IHR’s work with communities through research, policy engagement, and legal advocacy, particularly through its Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy Programme.

“Talking about Indigenous peoples is not talking about Indigenous peoples without asking them.”

Feminist Climate Justice Across Mindanao

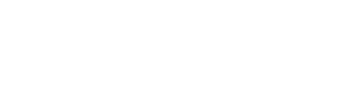

The forum opened substantively with Prof. Rufa Cagoco-Guiam, who framed climate change not as an environmental issue alone, but as a political condition shaped by inequality, conflict, and governance failure across Mindanao.

Drawing from research in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) as well as wider Mindanao contexts, Guiam described how climate impacts function as threat multipliers—intensifying existing vulnerabilities linked to poverty, gender inequality, weak institutions, and unresolved conflict.

Flooding, drought, environmental degradation, and resource scarcity, she emphasized, do not affect communities equally. Women, Indigenous Peoples, and marginalized rural communities bear the heaviest burdens, despite contributing least to environmental destruction. Meanwhile, corporate actors and political elites driving extractive industries and profit-oriented development remain insulated from harm.

Revisiting Barry Commoner’s laws of ecology, Guiam stressed that environmental destruction is never accidental. It is produced by systems of extraction, corruption, and state neglect.

“There is no such thing as a free lunch,” she said. “Environmental destruction always has a cost—and it is the poor who pay it.”

She argued for a feminist climate justice framework grounded in participation, accountability, and care—one that links climate harms to the principles of transitional justice: truth, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence. Climate justice, she insisted, cannot be separated from questions of land, militarization, and historical injustice in Mindanao.

Law, Naming, and the Politics of Indigenous Recognition

Building on questions of power and accountability, Atty. Raymond Marvic C. Baguilat, Head of the Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy Programme, examined how law itself has shaped—and often constrained—Indigenous identity.

Drawing from colonial history and critical legal theory, Baguilat argued that legal categories were historically designed not to recognize Indigenous peoples, but to manage land and resources. He recounted an encounter during fieldwork in Northern Mindanao where a community member rejected imposed labels:

“Hindi kami Indigenous Peoples. Kami ay Ubu Manuvu.”

The statement, he explained, was not a rejection of Indigenous identity but an assertion of self-definition over state-imposed categories. Naming, Baguilat emphasized, is never neutral—it reflects relations of power.

Tracing classifications such as “non-Christian tribes,” he showed how what he termed benevolent racism became embedded in law: policies framed as protection but aimed at control and assimilation. These logics persist today in overlapping land laws, extractive projects, and weak enforcement of Indigenous rights, even after the passage of the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA).

“If they use the name of their community, respect it. Recognition begins with listening.”

Indigenous Peoples, Baguilat stressed, are not recipients of rights granted by the state. They are peoples with inherent relationships to land, culture, and responsibility—relationships routinely undermined when land is taken without consent.

Marawi: Displacement, Autonomy, and an Unfinished Peace

Marawi emerged as the forum’s most urgent reminder that conflict does not end when fighting stops.

Speaking as an internally displaced person, Prof. Tirmizy E. Abdullah grounded the discussion in the fragile realities of Bangsamoro autonomy. Identifying himself as a bakwit, he spoke not as an academic, but as someone living the consequences of delayed justice.

“Today, I speak not as someone representing a university,”but as an ordinary Bangsamoro.”

Abdullah warned that repeated postponements of BARMM parliamentary elections, unilateral national government actions, and weakened peace mechanisms threaten the promises of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB).

“The CAB is not a gift from the state. It is the fruit of sacrifices—of blood, of struggle.”

More than eight years after the Marawi Siege, tens of thousands remain displaced. Accountability for deaths, disappearances, environmental damage, and the militarized rehabilitation process remains absent.

“Marawi is not only a humanitarian crisis,” Abdullah stressed. “It is a justice issue.”

That reality was echoed in the testimonies that followed.

Hanifa Pangcoga, also a survivor and member of the Reclaiming Marawi Movement, spoke of displacement as slow erosion—of livelihood, education, dignity, and security.

“Hindi kami dapat manatiling IDPs habang buhay.”

Mu-ahz P. Omar, a Marawi Siege survivor and IDP volunteer, rejected the framing of the siege as a closed chapter.

“Ang Marawi Siege ay hindi ‘event’—buhay namin ito. Sa kabila ng trauma at kawalan, narito pa rin kami. Buhay. Lumalaban. Umaasa. Hindi kami pinatay ng digmaan. Binuo kami nito.”

He described flight, loss, and years of life in “temporary” shelters that have become permanent, while entire barangays have been redeveloped without residents’ meaningful participation.

Together, their testimonies underscored that rehabilitation without return, participation, and accountability is not peace—it is prolonged injustice.

Bukidnon: Ancestral Land and the Persistence of Dispossession

From Marawi, the forum turned to Bukidnon, where Indigenous communities face a parallel struggle: dispossession that continues despite legal recognition.

Datu Rolando Anglao, Supreme Datu of the Manobo-Pulangiyon, testified to ongoing displacement even after securing a Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT). Private armed groups, extractive interests, and state inaction continue to block the community’s return.

“Ang lupa ay buhay.”

For the Manobo-Pulangiyon, land is not property but life itself—the basis of culture, sustenance, and identity. Yet agencies mandated to protect Indigenous rights have failed to enforce the law, exposing the limits of recognition without political will.

Youth, Education, and the Thread That Binds

The forum closed by returning to education—not as policy, but as resistance.

Angelika Moral, a Lumad youth shaped by community schools now forcibly shut down, honored Bai Bibyaon Ligkayan Bigkay and explained why Lumad education has long been targeted.

“Hindi kami tinuruan maging sunud-sunuran. Tinuruan kaming mag-isip.”

Recounting forced evacuation in Talaingod, Angelika drew clear connections between Lumad, Maranao, and Bukidnon struggles—displacement, land loss, silencing, and the criminalization of care.

“Iisa ang sugat. Iisa ang panawagan. Iisa ang laban.”

Education, she reminded the audience, is never neutral. It either reproduces injustice—or equips communities with the tools to remember, resist, and reclaim their future.

May Pag-asa Ba?

In the open forum, a young participant asked the question that lingered throughout the day: May pag-asa ba?

Prof. Guiam likened justice work to planting a tree—slow, patient, and rooted in continuity. Prof. Abdullah added that hope, especially in Islam, must never be abandoned. True hope, he said, lies in accompaniment—not symbolic or project-based solidarity, but staying until communities can return home.

Atty. Baguilat then turned the question back to the audience.

“Did you learn anything? Do you know why you needed to listen to these stories?”

The response was immediate and affirmative. Drawing the moment to a close, he underscored what the forum demanded of everyone present:

“May pag-asa. Bawal nang maging bulag.”

Beyond the Forum

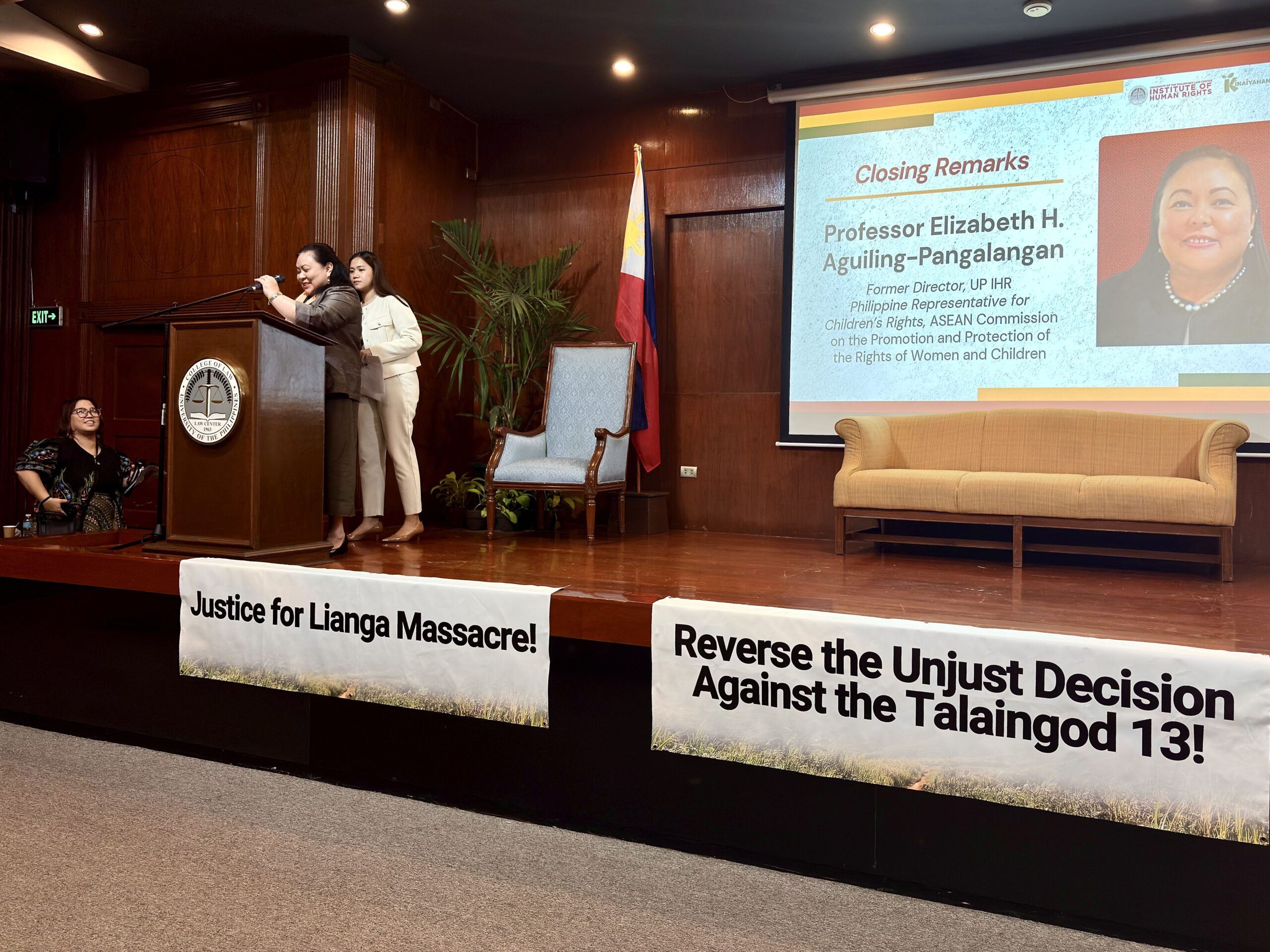

In her closing remarks, Prof. Elizabeth H. Aguiling-Pangalangan, former Director of UP IHR and Philippine Representative for Children’s Rights to the ASEAN Commission, reminded participants that the stories shared were not meant to be archived and forgotten.

Displacement, environmental destruction, and attacks on education, she said, are assaults on identity, culture, and future generations—particularly for Indigenous Peoples, women, and children. Human rights work, she emphasized, is not only about naming violations, but about nurturing resilience and walking alongside communities.

As the forum ended, one message remained clear: listening is only the beginning. Responsibility continues long after the room empties.