Not “Natural” Disasters:Extraction, Land Inequality, and the Political Production of “Bakwit Again” in Iligan City

“We were bakwit during the Marawi siege. Now we are bakwit again.”

Bai Rehan said it quietly inside a crowded evacuation center in Iligan City.

She fled once in 2017 when violence engulfed Marawi. Nearly a decade later, she was fleeing rising waters. The cause had changed. The displacement had not.

For Bai Rehan and her family, evacuation is no longer exceptional. It is recurring. First armed conflict. Now flood. Each crisis layered on top of the last.

Photo: MindaNews / Bobby Timonera)

Fifteen years after Tropical Storm Sendong devastated Iligan in 2011, the same communities once again fled rising waters during Tropical Depression Basyang in February 2026. Evacuation centers reopened. Families carried what they could. Children missed school. Livelihoods paused — again.

These are not natural disasters.

They are the foreseeable outcome of policies that reorganized forests, rivers, and land around commercial extraction and export growth — while concentrating environmental risk among the poorest communities.

When floodwaters repeatedly return to the same barangays, disaster is no longer unexpected. It is structured.

From Sendong to Basyang: A Pattern Foreseen

In December 2011, Tropical Storm Sendong (Washi) killed 1,268 people and affected nearly 700,000 nationwide, with Iligan among the hardest-hit cities. Entire riverside communities along the Mandulog River were swept away overnight.

Sendong was not the strongest storm to hit Mindanao. What made it catastrophic was the interaction between intense rainfall and landscapes already weakened by deforestation, land conversion, and settlement in flood-prone zones.

Post-disaster assessments identified watershed degradation, upland forest loss, river siltation, and poverty-driven settlement patterns as key drivers of flood severity. Hazard maps were produced. Risk zones were documented.

The knowledge existed.

Yet the underlying drivers — concession-based logging, large-scale commercial agriculture, extractive permits, and deeply unequal land distribution — were not fundamentally reversed.

Fifteen years later, Basyang brought more than 350 millimeters of rainfall upstream. National reports recorded approximately 467,000 people affected. In Iligan alone, over 1,200 families were displaced.

Early warning systems improved. Evacuations were faster. Fatalities were fewer.

But displacement returned — to the same floodplains, under the same structural conditions.

Disaster risk in Iligan is not accidental. It is the cumulative result of long-standing decisions about how land and natural resources are allocated — and whose interests those decisions prioritize.

What Basyang Revealed

Tropical Depression Basyang confirmed what communities have long understood: disasters are not caused by rainfall alone.

In a pastoral letter dated February 8, 2026, Bishop Jose Rapadas III of the Diocese of Iligan wrote:

“This disaster was not caused by rain alone. Its impact was worsened by long-standing environmental problems—denuded watersheds, silted and narrowed rivers, clogged drainage, and irresponsible waste disposal. When nature is abused, the consequences are borne most heavily by the poor and vulnerable.”

His reflection underscores a critical truth: environmental destruction does not affect everyone equally. It becomes catastrophic when combined with poverty, landlessness, and marginalization.

Extreme rainfall may be natural.

But disaster emerges when ecosystems are already weakened — when slopes once covered in mixed forest now channel water rapidly downhill — and when families have little choice but to live in hazard-prone areas because safer land remains inaccessible or unaffordable.

As MCJ Board Member Prof. Rufa Cagoco-Guiam emphasizes, climate disasters are governance crises. More fundamentally, they reflect long-standing development priorities that favored extractive industries and commercial interests over ecological sustainability. When policy repeatedly privileges short-term revenue and commodity growth over watershed protection, vulnerability becomes embedded in the landscape.

Watersheds Reorganized for Commodity Production

Large-scale logging in Mindanao intensified through state-issued Timber License Agreements. Companies such as Iligan Lumber Company and Nasipit Lumber Company operated under formal concessions. Timber extraction supported industrial expansion and national revenue goals.

This was development strategy.

Forests were treated as commercial assets rather than ecological infrastructure. Their role in regulating water flow and stabilizing slopes was subordinated to timber and industrial demand.

Today, Iligan retains roughly 35,000 hectares of natural forest. Yet approximately 200 hectares of tree cover continue to be lost annually. Across Lanao del Norte, about 11,000 hectares of tree cover disappeared between 2001 and 2024.

Floodwaters move across landscapes shaped by these choices.

Extraction generated revenue and employment. It contributed to economic growth. But it also reduced watershed resilience and transferred environmental risks downstream.

The benefits flowed upward.

The risks accumulated below.

Commercial Agriculture and Land Inequality

Northern Mindanao reflects decades of large-scale commercial agricultural expansion tied to global markets.

Across Mindanao, roughly 500,000 hectares are covered by plantations. Northern Mindanao accounts for over 127,000 hectares. Between 2005 and 2014, plantation areas expanded by approximately 79 percent.

This growth aligned with a national orientation toward export earnings and agribusiness investment.

Monocrop plantations simplified ecosystems and weakened watershed absorption capacity. Mining and quarrying operations further destabilized slopes and altered river systems.

At the same time, land ownership remains highly unequal. Many small farmers, Moro families displaced by conflict, and Indigenous communities lack secure access to safe land. Urban poor households are pushed toward riverbanks and floodplains — the only spaces within reach of livelihood opportunities.

Flood exposure follows land inequality.

Those who control land benefit from rising land values and export growth.

Those excluded from land absorb flood risk.

Disaster becomes the spatial expression of inequality.

Photo: Herman P. Salarda Jr.)

Climate Crisis and Moral Urgency

The Philippines contributes only a small share of global greenhouse gas emissions yet faces escalating climate vulnerability.

Climate change intensifies rainfall patterns. But rainfall alone does not determine who must evacuate repeatedly and who rebuilds in the same hazard zone.

Extreme weather interacts with landscapes reorganized for commercial extraction and communities marginalized by unequal land access.

As Fr. Rey Raluto of the Diocese of Malaybalay and the PANAAD Network warned:

“This is not just ecological decay; it is a climate emergency… When does climate emergency stop being a talking point and start being our urgent concern?”

When watershed degradation, commercial land transformation, and climate instability converge, displacement is no longer episodic. It becomes cyclical.

“Bakwit again” becomes the lived consequence of structural inequality.

Indigenous Stewardship and Structural Tensions

Across Mindanao, Lumad communities have long practiced rainforestation, community-managed water systems, and territorial zoning that safeguards headwaters.

These governance systems regulate land use, maintain ecological balance, and strengthen soil absorption — directly reducing flood risks in downstream communities.

But community-based territorial governance limits large-scale commodification of land. In areas near Bukidnon and Lanao uplands, ancestral domain protections often restrict logging, mining, and plantation expansion.

The marginalization of Indigenous territorial rights is therefore not incidental. It reflects structural tensions between ecological governance and extractive, export-oriented land use.

Strengthening Indigenous self-determination is not only a matter of justice. It is essential for rebuilding watershed resilience.

Environmental Defenders Under Fire: Mindanao as Ground Zero

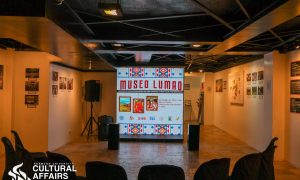

Photo: SOS Mindanao)

Environmental destruction in Mindanao has never gone uncontested.

For decades, communities have resisted logging, mining, plantation expansion, and fossil fuel projects. In 2015, residents from Lanao del Norte and Misamis Occidental undertook a multi-day climate walk opposing proposed coal-fired power plants near Iligan City. They warned of threats to fisheries in Iligan Bay and Panguil Bay, air pollution, and the long-term climate impacts of coal expansion. Today, many of the same communities that resisted coal development face recurring displacement from floods and environmental instability. The struggle against destructive energy projects and the struggle against recurring disaster are deeply connected.

But defending land and watersheds in Mindanao carries profound risks.

According to Global Witness research, the Philippines consistently ranks among the most dangerous countries in the world for environmental and land defenders. Between 2012 and 2023, Mindanao emerged as ground zero for attacks against Environmental and Human Rights Defenders (EHRDs), where mining, agribusiness expansion, logging, energy projects, and ancestral domain conflicts intersect.

This pattern has also been documented by a constitutional government body. The 2019 Haran Report of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) found that Lumad communities experienced militarization in ancestral domains, military presence in schools, displacement linked to armed conflict, and tensions associated with land and resource use. The CHR found that Indigenous communities were caught between armed actors in areas where extractive activity and territorial disputes overlapped . Environmental defense in Mindanao, therefore, unfolds within a landscape of structural insecurity.

Environmental and Human Rights Defenders in Mindanao include Indigenous leaders protecting ancestral lands, community organizers opposing destructive projects, church workers advocating ecological justice, volunteer teachers, youth climate mobilizers, and grassroots advocates documenting violations.

MCJ’s 2024 Mindanao Defender Protection Briefing recorded 92 extrajudicial killings, 227 cases of illegal arrest, detention, or abduction, 160 frustrated extrajudicial killings, 27 cases of torture, and 6 enforced disappearances affecting Indigenous communities and defenders in Mindanao. Between 2019 and 2021 alone, at least 45 Indigenous individuals were killed in connection with resource conflicts.

Violence, however, is only one dimension of the pressure defenders face.

Between 2014 and 2020, more than 200 Lumad community schools across Mindanao — including in Davao del Norte, Bukidnon, and Surigao del Sur — were shut down. These schools served thousands of Indigenous students in remote areas. They provided more than formal education; they offered collective spaces where young people learned about ancestral land protection, sustainable livelihoods, environmental stewardship, and self-determination. They enabled communities to analyze mining concessions, plantation expansion, militarization, and the ecological transformations reshaping their territories.

The closure of these schools removed one of the few institutional spaces where Indigenous youth could collectively understand land dispossession and environmental change — weakening long-term community capacity to defend watersheds and territorial rights.

Teachers and education advocates have likewise faced harassment, criminalization, and Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPP). The Talaingod 13 case demonstrates how legal processes can be used to exert sustained pressure on those engaged in community-based education and land rights defense.

These patterns are not incidental. Suppressing environmental defense stabilizes a development model dependent on uninterrupted extraction and centralized control over land and natural resources.

Where extractive projects expand into ancestral domains, militarization often follows.

Where communities assert territorial rights, defenders face surveillance, vilification, or violence.

Where schools teach environmental stewardship and self-determination, they are treated as security concerns.

Disaster in Mindanao is not produced only by degraded ecosystems. It is reinforced when the people working to protect forests, rivers, and ancestral lands are silenced.

When defenders are pressured, extraction proceeds.

When extraction proceeds unchecked, watersheds erode.

When watersheds erode, flood risk intensifies.

And families evacuate — again.

Protecting Environmental and Human Rights Defenders — including educators and land rights advocates — is inseparable from protecting communities from recurring displacement and climate vulnerability.

Relief Without Structural Reform

Photo courtesy of SAMIN / Laudato Si Network)

In February 2026, MCJ and partner networks conducted relief missions in affected barangays, distributing essential supplies to displaced families.

Relief is necessary. It saves lives.

But relief does not restore forests, redistribute land, or reform concession systems.

Without meaningful transformation in watershed governance, equitable land access, and development priorities, evacuation centers will reopen.

Managing disaster without transforming its structural drivers only stabilizes vulnerability.

This Is a Question of Power

Floods in Iligan are not natural disasters.

They are the cumulative outcome of state-sanctioned forest extraction, commercial land conversion, unequal land distribution, and governance systems that prioritized capital accumulation over ecological security.

Climate change intensifies rainfall.

Extraction intensifies runoff.

Inequality determines who bears the loss.

Disaster is intensified by rain.

Displacement is intensified by inequality.

Breaking the cycle of “bakwit again” requires confronting entrenched land concentration, reforming concession-based resource governance, strengthening Indigenous territorial rights, and reorganizing development priorities around ecological integrity and community security rather than short-term export revenue.

Until that shift occurs, evacuation centers will reopen.

And families will continue to say: