“‘Sorry, You Are Weak’? Structural Exposure and the Mental Health of Young Filipinos”

In a widely reported interview, Senator Robin Padilla told young Filipinos, “Sorry, you are weak,” contrasting them unfavorably with older generations at a time of rising public concern over depression and suicide.

The statement framed youth distress as a matter of character. Yet mounting evidence points to something more complex: prolonged economic strain, educational disruption, climate shocks, and uneven access to support systems that shape daily life.

When psychological distress rises across entire cohorts in measurable and patterned ways, the issue is not character. It is condition.

Growing Up in Protracted Uncertainty

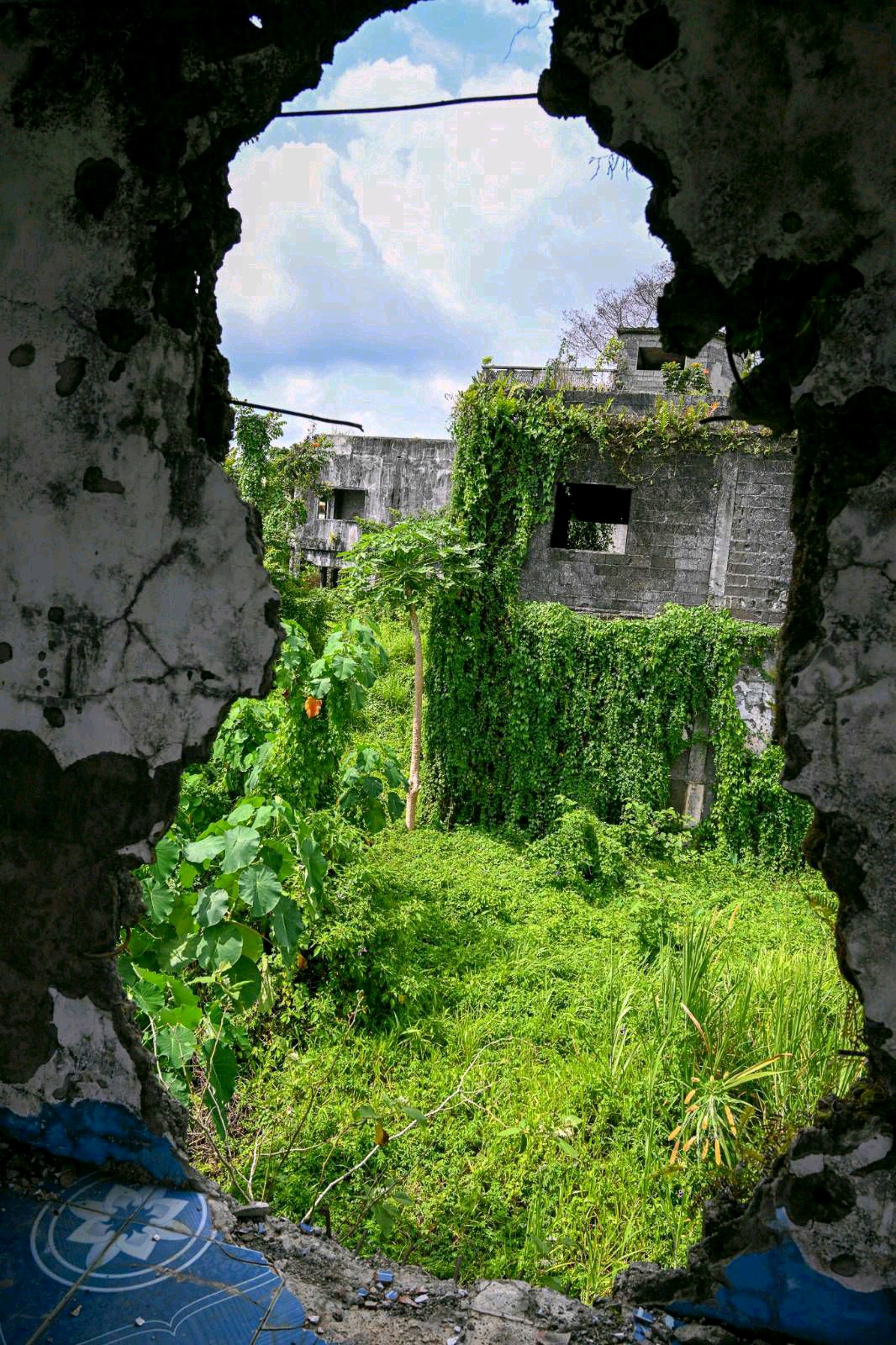

At night in a temporary shelter in Marawi, seventeen-year-old “Amirah” studies beneath a flickering bulb powered by an extension cord that may be unplugged without notice. A generator hums in the background. Water stains climb the walls — reminders that disaster here is not a passing episode. It is an environment.

Nearly eight years after the 2017 siege, large sections of the city remain under restricted reconstruction. Amirah was still a child when the fighting began. Much of her adolescence has unfolded in displacement. Her family’s home lies within a zone where rebuilding has been slow and tightly regulated. Compensation claims were submitted, inspections conducted, and years moved forward. Many families continue to live in temporary housing while rehabilitation advances incrementally.

“Sanay na po kami sa paghihintay,” she says. We are used to waiting.

In Marawi, waiting has become procedural — structured through documentation, verification, and delayed approvals. Time is measured in follow-ups, assessments, and uncertain timelines.

Amirah dreams of becoming a public school teacher. Since 2017, however, she has not spent more than one uninterrupted year in a stable classroom. Evacuation centers, transition sites, interrupted calendars — her education has arrived in fragments.

When she describes herself as pagod sa isip — tired in the mind — she is not referring to a single moment of stress. She is describing years of accumulated disruption: unstable housing, interrupted schooling, and prolonged uncertainty.

Her experience does not stand alone. It reflects how protracted instability shapes a generation.

The Data Shows a Structural Pattern

If youth distress were merely a matter of individual fragility, it would appear sporadic and isolated. Instead, national data show sustained increases across populations and over time — a pattern that suggests broader structural drivers.

A nationwide study published in Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health found that moderate to severe depressive symptoms among Filipinos aged 15–24 more than doubled between 2013 and 2021, rising from approximately 9.6% to 20.9%. Nearly one in five young people reported seriously considering suicide. A shift of this scale over less than a decade signals conditions affecting large cohorts, not isolated cases.

Public reporting citing Department of Health figures noted nearly 2,000 recorded suicide cases in the first half of 2025 alone, reflecting the continuing gravity of the issue. Beyond mortality statistics, national and international estimates indicate that millions of Filipinos live with mental, neurological, or substance use conditions that affect daily functioning — many without consistent access to care.

At the global level, the World Health Organization reports that more than one billion people live with mental health conditions worldwide. Among adolescents, depression and anxiety are leading causes of illness and disability, underscoring that youth mental health challenges are neither rare nor trivial.

Taken together, these findings point to a consistent pattern: psychological distress is increasing in measurable ways that align with prolonged social disruption, economic strain, and environmental instability. When increases occur across time, geography, and demographic groups, explanations must extend beyond individual character to the conditions shaping daily life.

Everyday Pressures That Accumulate

Psychological distress does not arise only from dramatic events. It also builds through ordinary conditions that persist day after day.

These pressures are structural and interconnected.

Economic precarity remains a defining feature of daily life for millions of Filipino families. Official data from the Philippine Statistics Authority show that poverty incidence continues to affect a significant portion of households. Even among those above the poverty threshold, rising food prices, transport costs, tuition, utilities, and housing expenses compress already thin margins. Financial uncertainty requires constant adjustment — decisions about which expenses to defer, which needs to prioritize — producing chronic stress rather than episodic crisis.

Educational instability compounds this strain. The EDCOM II Final Report documented severe learning gaps nationwide, with nearly half of learners not meeting expected reading levels and many falling below minimum mathematics benchmarks. Dropout risks are highest in economically vulnerable communities. For young people, academic disruption is not merely academic; it affects confidence, future prospects, and perceived mobility.

Urban mobility pressures add another layer. In major cities such as Metro Manila and Davao, prolonged traffic congestion consumes hours daily that might otherwise be spent resting, studying, or engaging with family and community. Time scarcity becomes routine, eroding recovery and increasing fatigue.

Climate and geophysical hazards further intensify uncertainty. In 2025 alone, 23 tropical cyclones entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility, displacing families and disrupting schooling and livelihoods. In October 2025, twin earthquakes in Davao Oriental damaged homes, schools, and infrastructure, compounding stress in already vulnerable communities.

These forces do not operate independently. Economic insecurity limits adaptive capacity. Educational disruption narrows perceived opportunity. Repeated disaster exposure embeds anticipatory anxiety. Recovery is often partial before the next shock arrives.

Over time, uncertainty becomes continuous — not an interruption of normal life, but part of it.

Climate Change Is Also a Mental Health Issue

Climate disruption intensifies psychological risk.

A growing body of research links exposure to extreme weather events — floods, typhoons, droughts, and heatwaves — to higher rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and prolonged emotional distress. The World Health Organization has identified climate change as a “threat multiplier” that amplifies existing health vulnerabilities, including mental health risks, particularly in disaster-prone and low-resource settings.

These impacts operate through identifiable pathways. Repeated displacement disrupts schooling and livelihoods. Delayed rebuilding prolongs uncertainty. Loss of homes, land, and community infrastructure erodes predictability and social cohesion. Anticipatory anxiety about future disasters becomes embedded in everyday life.

In the Philippine context, psychologist John Jamir Benzon Aruta has emphasized that climate-related disasters produce not only immediate trauma but cumulative emotional effects — including grief, climate anxiety, and persistent worry about recurrence. He has called for integrating climate adaptation planning with mental health systems and strengthening community-based psychosocial support, especially in vulnerable regions.

International research reinforces these findings. A global survey of young people published in The Lancet Planetary Health documented widespread climate-related distress, with many youth reporting that climate change affects their daily functioning, sense of safety, and outlook for the future.

In Mindanao — where tropical cyclones, flooding, displacement, land conflict, and extractive expansion intersect — climate stress does not occur in isolation. It compounds pre-existing structural vulnerabilities. Communities with limited resources for relocation, rebuilding, or adaptation face repeated exposure. Those with greater economic and political capacity are better positioned to buffer disruption.

The psychological consequences, therefore, are not evenly distributed. They follow lines of inequality.

Mindanao: Parallel Burdens, Shared Strain

In Mindanao, the weight of instability takes different forms across communities.

Local reporting from the Southern Philippines Medical Center documented at least 64 suicide attempts in the region in 2025, many linked to depression and psychosocial strain. At the same time, access to specialized care remains limited. Out of roughly 673 psychiatrists nationwide, only about 41 practice across Mindanao — a region home to more than one-fifth of the country’s population.

The numbers point to strain. But they do not fully explain it.

In Marawi, young people continue to navigate prolonged displacement and delayed reconstruction nearly eight years after the siege. Education, housing, and restitution remain uneven and incomplete.

Within Lumad communities, the burden has taken another form.

Angelika Moral, a Blaan youth leader and former Lumad student, grew up amid the militarization of ancestral lands and the closure of Lumad community schools. As schools faced red-tagging and legal charges, volunteers organized support for displaced children and sustained community-based education under pressure.

The conviction of the Talaingod 13 — educators and volunteers associated with Lumad schools — placed additional strain not only on those directly involved, but on youth who viewed community education as central to dignity, cultural continuity, and self-determination.

For Lumad youth, instability has meant navigating land conflict, legal uncertainty, and militarized environments. For Moro youth in Marawi, it has meant bureaucratic waiting and incomplete restitution.

The contexts differ, but the cumulative psychological load is comparable.

Neither Amirah nor Angelika withdrew. Both continued studying, organizing, and advocating within constrained environments shaped by structural instability.

Mental Health Is Political — and Collective Care Is Structural

At MCJ, we affirm that mental health is political — not in a partisan sense, but because well-being is shaped by systems. Land policy, economic inequality, governance priorities, climate vulnerability, and access to social protection determine who is protected from instability and who is repeatedly exposed to it. When exposure is patterned, distress is patterned.

Dr. Reggie Pamugas, community mental health practitioner and member of MCJ’s Board of Trustees, notes that chronic instability conditions the nervous system toward hypervigilance. The body adapts to sustained uncertainty not because individuals are weak, but because environments repeatedly demand survival responses. For young people growing up amid displacement, militarization, climate shocks, or legal insecurity, these physiological adaptations become normalized — even when the structural causes remain unaddressed.

Ms. Meg Yarcia, psychologist and advisory member to MCJ’s Board, emphasizes that mental health rests on material and relational foundations: land security, community cohesion, educational continuity, and access to safe and predictable spaces. When these foundations erode, whether through conflict, delayed reconstruction, economic precarity, or environmental disruption, psychological strain is not incidental. It reflects systemic instability.

These insights shape MCJ’s Panalipod Training Framework, which approaches mental health through a political economy lens. The framework examines how unequal development distributes psychological risk and why collective care — including psychosocial support, defender protection, and community-based resilience — must be integrated into climate justice and human rights work as core strategy, not supplementary service.

Returning to the Claim

If young Filipinos appear exhausted, it is not because they lack resilience. It is because they have adapted repeatedly to instability — economic, climatic, educational, and political — often without adequate institutional support.

The more urgent question is not whether youth are weak, but whether our institutions are structured to absorb instability — or to pass it downward.

What appears as fragility may, in fact, be prolonged exposure to uncertainty.

And systems — unlike generations — can be redesigned, repaired, and rebuilt.